Shortest X-ray exposure of tiny biological crystals

Protein Nanocrystals Form a Time Switch for Diffraction

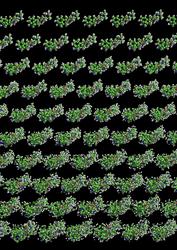

A protein crystal consists of a regularly ordered array of protein molecules. The molecular structure is determined from the pattern of X-ray light (called a diffraction pattern) that is scattered from this periodic array. Unider illumination from an ultra-intense X-ray pulse from a free-electron laser the crystal explodes. This initiates as an atomic disordering of all the constituent molecules. As this disorder increases in time (which flows down the picture) the crystal loses definition initially at the highest resolution, and later at lower resolution, causing a corresponding termination of the detected diffraction. Even if pulses are much longer than the explosion timescale, the measurement corresponds to the undamaged molecule.

An international research team headed by DESY scientists from the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science (CFEL) in Hamburg, Germany, has recorded the shortest X-ray exposure of a protein crystal ever achieved. The incredible brief exposure time of

0.000 000 000 000 03 seconds (30 femtoseconds) opens up new possibilities for imaging molecular processes with X-rays. This is of particular interest to biologists, but can be employed in many fields, explain lead authors Dr. Anton Barty and Prof. Henry Chapman from the German accelerator centre Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron DESY. CFEL is a joint venture of DESY, the Max Planck Society and the University of Hamburg.

From X-ray diffraction the molecular structure of proteins can be determined. The shorter the X-ray pulse and the higher its intensity, the better the structural information gained. With the free-electron laser Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) at the US Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) the research team fired the most intense X-ray beam at a protein crystal to date: The tiny crystal was bombarded with a whamming 100 000 trillion watts per square centimeter – sunlight for comparison comes in at a mere 0.1 watts per square centimeter on average. “This way we get the most information out of the smallest crystals,” Chapman explains. Having small crystals is important, as especially many biological substances aren´t easily crystallized.

The emerging technology of X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) promises to deliver scientific breakthroughs in many areas. One of these areas is biology, where ultra-short X-ray pulses of unprecedented power from XFEL sources open up the possibility to obtain the three-dimensional structures of entire classes of proteins that could not be previously measured.

Structural biologists widely rely on the technique of protein X-ray crystallography, where X-rays scattered from protein crystals form a so-called diffraction pattern. Scientists use these patterns to reconstruct a detailed atomic picture of the protein molecule. However, radiation damage is a major concern when working with very intense X-rays. The research team now reports that these crystals produced high-quality diffraction patterns although the crystals’ lifetime in the XFEL beam was much shorter than the used XFEL pulses (Nature Photonics, Advanced Online Publication, 18 December 2011). The use ofnanosized crystals also shows how to overcome one of the largest bottlenecks in structural biology, which is the long and often unfruitful process of growing high-quality protein crystals of sufficient size.

XFELs produce X-ray pulses that are so intense that any sample in the focused beam is completely vaporized. This explosion begins within several femtoseconds. However, researchers were able to obtain diffraction patterns from protein nanocrystals using significantly longer pulse lengths. “It was not at all obvious how this was possible,” says Henry Chapman from CFEL. “All the theories predicted that we should use pulse lengths of about 10 femtoseconds. But even though we increased the pulse lengths to over 300 femtoseconds and deposited over a hundred times more radiation dose than assumed acceptable, we could still see high-quality diffraction patterns.”

At first, these results appear to be counter-intuitive. “The key to understanding our unexpected results iscrystallinity,” explains Chapman. In a crystal, the same structural element, the unit cell, repeats many times in several directions. Due to this structure, X-rays going through a crystal do not scatter uniformly in all directions, rather intense bundles of light emerge from the crystal only under specific angles – forming the diffraction pattern. “If the correlation between unit cells is lost during the explosion of the sample in the XFEL beam, then diffraction no longer occurs,” says Chapman. In other words, diffraction terminates once the crystal is destroyed, and any X-rays hitting the sample after this time do not contribute to the diffraction pattern initially recorded. Remarkably, the apparent measurement pulse is shorter than the incident pulse length: it is as ifnanocrystals form a time switch that turns diffraction off once enough useable data is collected.

If the explanation is so straight-forward, you may ask, why has this effect not been observed before? AntonBarty from CFEL explains that the mechanisms of X-ray damage at conventional synchrotron and novel XFEL light sources are completely different. “At a synchrotron, everything happens comparatively slowly and there is time for chemical damage to occur. At an XFEL, however, the sample turns into plasma within a few femtoseconds. This is faster than any bond breaking mechanisms previously seen in synchrotron experiments. ”Indeed, during the first phases of the explosion the atoms virtually stay in their place, held in place by their own inertia, and a high-quality diffraction pattern can be recorded. Theoretical calculations performed by fellow CFEL scientist Carl Caleman agree amazingly well with the experimental observations.

The outcome of this research benefits developments in X-ray crystallography, which is a key technique to determine protein structures. Knowledge of these structures is essential for an understanding of life’s functions and malfunctions. For biopharmaceutical companies, for example, X-ray crystallography is an important contributor to drug development. However, certain proteins, such as membrane-embedded proteins, are difficult to crystallize or they only yield crystals too small to investigate at a synchrotron. “Our ultra-fast, ultra-intense XFEL experiments on very small protein crystals show that, in the very near future, we will obtain atomic resolution structures of systems that have been very challenging so far,” says Henry Chapman.

The future is bright. With the European XFEL currently being built in Hamburg, the world’s most powerful XFEL will start its operation in 2015. “With our technique we need about one million X-ray pulses to determine a protein structure,” Chapman says. “Currently, this is a matter of hours. At the European XFEL facility it will be a matter of minutes.”

Manuel Gnida