Innovative accelerator project produces first particle beam

Milestone on the path to laser-driven plasma accelerators

An innovative accelerator project at DESY has produced its first electron beam. The experimental facility goes by the name of LUX and is being operated in collaboration with the University of Hamburg. It is based on the promising technology of plasma wakefield acceleration which will hopefully one day give rise to smaller and more powerful particle accelerators. The experimental LUX accelerator was developed and built by a junior research group headed by Andreas R. Maier, located at CFEL. The junior research group is part of the accelerator physics group at the University of Hamburg, led by physics professor Florian Grüner. However, the new technology still has to overcome a number of hurdles before it can be used in accelerators.

During a first test run, LUX was able to accelerate electrons to about 400 mega-electronvolts, using a plasma cell that is just a few millimetres long. This corresponds very nearly to the energy produced by DESY’s 70-metre, linear pre-accelerator LINAC II. “The result is a first important milestone on the path to developing compact laser/plasma-based accelerators in Hamburg,” explains Reinhard Brinkmann, Director of the Accelerator Division at DESY.

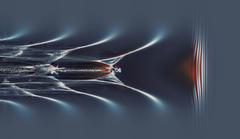

In plasma wakefield acceleration, a wave is produced in an electrically charged gas, known as a plasma, inside a narrow capillary tube. There are several different ways of doing this, which are being tried out in various projects on the DESY Campus in Hamburg. “LUX uses a laser with a power of 200 tera-watts, which fires ultra-short pulses of laser light into the hydrogen gas,” says Maier from the University of Hamburg. Each pulse lasts a mere 30 quadrillionth of a second (30 femto-seconds) and ploughs its way through the gas in the shape of a narrow disk: the light pulses are just 0.01 millimeters long and 0.035 millimeters high. “They snatch the electrons from the hydrogen molecules, just as a snow plough sweeps aside snow,” the physicist explains. “The electrons collect in the wake of the light pulse and are accelerated by the positively charged plasma wave in front of them – much like a wakeboarder riding the stern wave of a boat.” The special laser at the ANGUS laser laboratory is able to produce a particularly high frequency of up to five pulses per second.

The physicists surrounding Maier are hoping to use this technology to accelerate particles to up to 1000 mega-electronvolts. “The technology is still in the very early stages of development,” says Maier, “but as it is able to produce up to 1000 times the acceleration of conventional accelerators, it will allow us to build far more compact accelerators for future applications in fundamental research and in medicine.” However, he notes that “if the new technology is to be put to practical use one day, we need to optimize it, which is something we can only do in collaboration with the accelerator experts at DESY.”

LUX is operated as part of the LAOLA cooperation between the University of Hamburg and DESY, in which various groups from these two institutions work together closely to study pioneering new accelerator designs. Another important partner is the ELI Beamlines project in Prague (Czech Republic). Over the coming months, the accelerator physicists will examine and further optimize the as yet “untidy” electron beam produced by LUX. To this end, the apparatus will be extended by adding further measuring equipment for so-called beam diagnostics. Furthermore, the researchers are planning to install a short magnetic slalom course, a so-called undulator, in order to test whether the fast electrons from the plasma accelerator can be used to produce x-rays.

LUX homepage: lux.cfel.de